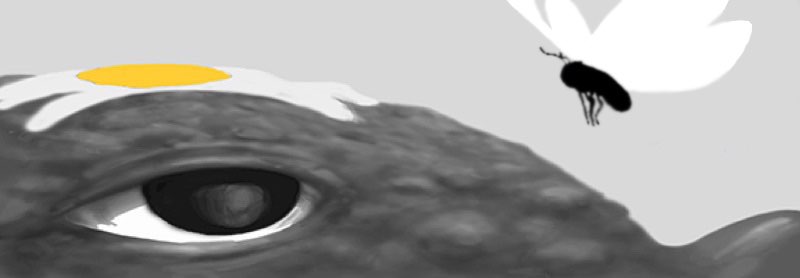

Named for their distinctive dorsal marking and only known habitat—a few miles north along Nottawasaga Bay from Meaford, my home town—the now-extinct Nottawasagan Daisybacks are the only species of toad ever known to cooperate with one another in the capture of prey. Their modus operandi?Sharing the chameleon’s ability to blend with their environment, only their ‘daisies’ were visible amid the stones and tall grass of their shoreline habitat where, in small bands, they’d arrange themselves within striking distance of one another and spear duped insects off one another's backs with their sticky tongues.

According to local records, they were first discovered in the Spring of 1942 by two young brothers* from Toronto who, being unacquainted with toads, assumed these were typical, so made nothing of it. A full year would pass before they were discovered a second time, but this time, wittingly—a full year of quiet before the storm, as it turned out.

Though the Meaford Express was first to break news of their discovery, it was, by most accounts, a front-page article about them in the June 17th 1943 issue of the Owen Sound Sun Times that sparked the firestorm of public interest that, within weeks, saw our Daisybacks go from hopping about in obscurity to hopping across the front pages of newspapers from coast to coast—up one side of the U.S. border and down the other. Then onto the covers of Life, and Look, and National Geographic, and a whole slew of other publications, as well. And that wasn’t the half of it, for, by now, larger-than-life radio personality, Gordon Sinclair, was breaking audience records, both here and abroad, with his controversial “Daisybacks Forever” broadcasts; and religious leaders of all denominations were crafting sermons around them; and big-name comedians like Burns & Allen and Edgar Bergen were writing them into their routines. Bob Hope, too. And then came President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s September ’43 Fireside Chat, in which, to an estimated 60 million listeners, he professed a personal fascination with our Daisybacks and famously declared their co-operative ways “an example to mankind we’d do well to follow.”

We’d been thrust into the limelight and community pride was through the roof, but there was no time for basking, for with all this attention came challenges, the most immediate being the challenge of accommodating the sudden deluge, into our quiet little bayside community, of all manner of people from all over—scientists, educators, journalists, photographers, sightseers, tourists, politicians, developers, even a couple of big-shots from Hollywood. And then came the fishermen, for as the world learned of our Daisybacks, it learned, also, of our abundant lake trout. One of my earliest memories, ever, is of cars and people, all day long, everywhere I looked. It might have been disastrous, but the townsfolk were not only up to the challenge, they were hungry for it and, in a matter of months, Meaford was boasting the largest fresh-water fishing fleet in the world and had been ranked Canada’s third-largest tourist attraction.

If you were a resident during these times, you prospered, simple as that. It was harder not to. Even so, not everyone welcomed the change and, even among those who did, emotions were mixed. World War II was raging in the background and many, especially those with a personal stake in it, were not easily cheered by prosperity. For most, however, life had never been better and, in the summer of ‘45, when the guns fell silent, never been better became even more so.

I loved those times. Every day, something new and exciting. I still have an old photo I clipped from the Meaford Express of Hopalong Cassidy on Topper trotting down the main street of Meaford with a whole bunch of us kids chasing after him. They were, hands down, the best years of my life. Exciting times, for sure, to be a kid in Meaford. It was a bit like living in a carnival.

Sadly, as all best years must, these and the best years of many others, I’m sure, came to an end the summer of ’48, when, without warning, the Daisyback population, which, till then, had been steadily increasing, took a sudden plummet. Within three days, their numbers had declined by nearly a third. People were starting to panic. Their livelihoods were disappearing right before their eyes, and fast.

But then, on the morning of the fourth day, came reassuring news. To a council chamber crowded-to-overflowing with anxious citizens, the Mayor announced that help was on the way, that an investigative team led by University of Toronto’s Chief Herpetologist, Hugh Percival, had been assembled and was expected to arrive later that same day. Percival, he said, was a giant in his field and if anyone could help us, he could.

Percival and his team were not long discovering the problem and to a quickly-convened Council delivered troubling news—the Daisybacks’ distinctive dorsal markings had been seriously corrupted** and there were many could no longer attract prey for others. The situation was already critical, said Percival, and there was no time to waste. As a first step, all the Daisybacks would have to be rounded up and those with corrupted markings separated out.

The next morning, while town officials roped off the Daisybacks’ habitat, teams of volunteers were assembled and equipped and, by noon, the roundup had begun. All going well, they expected to finish by the weekend, and some thought even sooner.

But all did not go well. The weather, almost immediately, turned freakishly cold and rainy and stayed that way, on and off, for several days, for most of that time rendering the rocky shoreline too treacherous to navigate. And freakish weather wasn’t their only challenge—the Daisybacks were excreting a layer of slime that made them nearly impossible to hold onto. By week’s end, only a few had been captured and spirits were low. Then, further darkening the mood, tragedy struck—two popular young local boys drowned in a capsizing just offshore from the roundup. For days after, no one cared much about toads and, by the time they did, it was too late—our Daisybacks were well on their way to extinction.

This first blow to the local economy was followed, several years later, by the arrival in Georgian Bay of the Lamprey Eel, which, in the span of a few more years, killed off the lake trout. Though losing our Daisybacks had hurt us in a big way, the fishing business had continued to flourish and, though less grandly, life had gone on. Now, however, with the lake trout also gone, vacationers were easily drawn elsewhere and, before long, the streets were empty, the fishing boats gone, the hotels put to other uses.

Today, these many years later, the once-bustling harbour provides shelter for sailboats and, apart from a few faded photographs in a glass case at the back of the local museum, little trace remains of the toads that once earned Meaford a brief appearance on the world stage.

Of the books they inspired, “Daisies Come and Daisies Go” by area resident, Herbert Clement Appleyard, remains my favourite. It was Roosevelt’s favourite, too. He kept a copy by his bed.

* While Toronto brothers, Alan and Peter Williams, are generally credited with discovering the Daisybacks, some argue that an unwitting discovery is not a discovery and give full credit, instead, to Meaford boy, Andrew Laycock, who, on May 24, 1943, was the first to discover them wittingly.

-

** The cause of the corruption remains unresolved. Some hold to the notion that our Daisybacks interbred with non-Daisybacks. Others argue, as did Percival, that corruption happened far too quickly for that to have been the cause. Though interest in this matter has waned over the years, the larger issue of how our Daisybacks could have evolved in the first place and escaped notice for so long is occasionally debated, still, by evolutionists and their detractors. Unsurprisingly, the mysteries surrounding their apparently brief existence have, over time, spawned a good number of conspiracy theories, many of them claiming that our Daisybacks were of another world. Though no fan of conspiracy theories, I’ve wondered, myself, if they were.

the Daisybacks